Anna Mertz

Rhino saviour

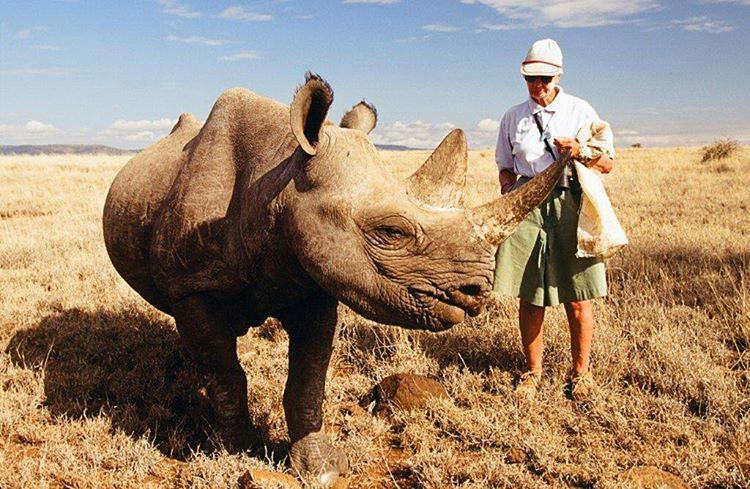

Anna Mertz (& the Craig family at Lewa)

Desmond Morris once said that "she was to rhinos what Joy Adamson was to lions, Dian Fossey to gorillas, and Jane Goodall to chimpanzees. And to the world at large, she will forever be known as the “mother of rhinos.”

Anna Merz was a fearless woman. Born Florence Ann Hepburn Fawell near London in November 1931, she first trained as a lawyer before giving in to her passion for adventure and setting off for Ghana. There she met her first husband, Ernest Kuhn, the Swiss owner of an industrial workshop. Anna ran the business, trained racing ponies and worked as an honorary warden for the Ghana Department of Game and Wildlife, surveying sites for wildlife reserves and managing an animal orphanage.

After her divorce from Kuhn, Anna married Karl Merz, and together they explored Uganda and Kenya, where they settled in 1976. It was there that she started her campaign to protect the country’s rhinos. Later, she retired to South Africa where she continued to be involved with the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy as a member of its board of directors and as a fundraiser, went horseriding regularly and enjoyed her eight beloved dogs. Her courage in the face of danger was astonishing: in Ghana she killed a Gaboon viper with her father’s cavalry sabre; in Kenya she killed a cobra with a rake, though not before it had spat a jet of poison at her; and in South Africa she shot dead two pythons that she had found trying to devour her dogs. For her work with rhinos, Anna Merz was awarded the Global 500 Award from the UN Environment Programme. She died in South Africa on 4 April 2013. (Courtesey Dale Morris and Africa Geographic)Lewa Wildlife Conservancy is what it is today because of a lady called Anna Merz, a dear friend of David and Delia Craig. She approached them in the early 80s with a request: horrified by the population decline of rhino throughout Africa, Anna wanted to build a rhino sanctuary to protect the last remaining members of the species. At this point in time, demand for rhino horn had reduced Kenya’s 20,000 rhino to a few hundred in less than 15 years.

The partnership between Anna and the Craigs led to the creation of the Ngare Sergoi Rhino Sanctuary, a fenced and guarded 5,000-acre refuge at the western end of Lewa Downs. In less than a year they were given permission from the Kenyan government to collect all of the rhinos they could find still living in the wild in northern Kenya and formed security and wildlife supervision teams to manage their protection. The breeding program and conservation were extremely successful and began attracting tourists from around the world, anxious to see some of the last remaining rhinos in Kenya. Despite being a vast expanse of protect habitat, Lewa was surrounded by unprotected land and the only way conservation efforts in the area would sustain was if local people could see tangible benefits resulting from the work.As reported in the New York Times, Merz “left no immediate survivors, but more than 70 black rhinos, including one born the day she died, continue to thrive in the sanctuary that she created to protect them from poachers, who kill the animals for their horns.” That sanctuary, which she founded in 1981 in response to encountering murdered rhinos in Kenya, began as the Ngare Sergoi Rhino Sanctuary, evolving and growing into what would be renamed the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in 1995.

(Courtesy: lewawilderness.com/)

ARTICLE IN NEW YORK TIMES CELEBRATING THE LIFE OF ANNA MERTZ

Anna Merz, who went to Kenya seeking a serene retirement but became so appalled by the slaughter of black rhinoceroses that she helped start a reserve to protect them, becoming a global leader in the fight against their extinction, died on April 4 in Melkrivier, South Africa. She was 81.

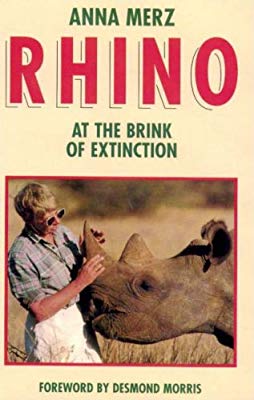

The Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, the reserve she founded, recently announced her death. She left no immediate survivors, but more than 70 black rhinos, including one born the day she died, continue to thrive in the sanctuary that she created to protect them from poachers, who kill the animals for their horns. As a young woman, Mrs. Merz roamed the world and ended up in Ghana, where she married twice, ran an engineering firm and became active in wildlife conservation. She and her husband went to Kenya to retire, but her revulsion at seeing the carcasses of rhinos strewn about a national park, each missing its distinctive double horn, compelled her to change her plans. She started looking for land to use as a rhino reserve and, after many rejections, found a patron, David Craig, who with his wife, Delia, owned a vast tract in the shadow of Mount Kenya. They agreed to set aside 5,000 acres for the project, which opened in 1981 as the Ngare Sergoi Rhino Sanctuary. It has since grown to 61,000 acres through more land donations and was renamed the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in 1995. Lewa’s success helped the black rhino population double to 4,880 over the last decade, still a far cry from the millions that once roamed Africa. Lewa is home to 10 percent of Kenya’s black rhinos, and its efforts have lent substance to the dream of returning the species to its former dominance in northern Kenya. Lewa rhinos must be regularly resettled elsewhere because the success of the breeding program — the reserve’s numbers grow 10 percent a year — has caused overcrowding and fights. Mrs. Merz’s example has inspired other wildlife conservation efforts and has helped make the black rhino, which is still critically endangered, a global symbol of extinction prevention. “I have met many remarkable animal specialists during my life, but none as extraordinary as Anna Merz,” Desmond Morris, the zoologist and author, wrote in the foreword to her 1991 book, “Rhino at the Brink of Extinction.” “What Joy Adamson was to lions, Dian Fossey was to gorillas, and Jane Goodall is to chimpanzees, Anna Merz is to rhinos.” Florence Ann Hepburn was born in Radlett, England, on Nov. 17, 1931, and moved between London and Cornwall as a child. A formative experience was seeing a museum exhibit on the dodo, which is believed to have become extinct in the 17th century. Another was being on a beach at age 9 when a German fighter plane attacked: a total stranger threw his body on top of hers and died saving her life. She graduated from Nottingham University, studied law and traveled to exotic places before settling in Ghana. There she married Ernest Kuhn, whom she divorced in 1969, and Karl Merz, who died in 1988. Both husbands were Swiss. In Ghana she trained and rode racehorses, rescued chimpanzees and was named an honorary game warden by the nation’s game department. She and Mr. Merz moved to Kenya in 1976. After securing the first 5,000 acres for the reserve, Mrs. Merz, using her inheritance, built an eight-foot-high fence, then began rounding up rhinos using helicopters and stun guns. She hired more than 100 armed guards, bought a plane for surveillance and built a network of spies to inform on poachers. Poachers, also armed, sell the horns largely to Asians, who grind them for folk medicine, and Arabs, who carve them to use as dagger handles. Prices for rhino horns can run higher than those for gold. “These are very ruthless people,” she said of poachers. Mrs. Merz herself carried a gun and knife. Deborah Gage, a conservancy official in London, wrote in an e-mail that about a year ago Mrs. Merz heard a yelp and “went into the next-door room to find that a python had taken her favorite dog, so she grabbed her pistol, shot the python in the head and gradually unraveled it off her dog.” At first Mrs. Merz used her own money to finance the project, a total of more than $1.5 million, but she came to rely on donations. The American Association of Zoo Keepers helped by raising millions for rhino preservation through its annual “Bowling for Rhinos” campaign. Winners spent a week with Mrs. Merz at her reserve. Giving local people a stake in the reserve was crucial to its success. She employed them, built schools and medical clinics for them and helped foster the tourist industry. Besides rhinos, of both the black and white species, visitors come to see lions, elephants and other animals. Prince William of Britain and Kate Middleton became engaged in 2010 while staying at a cottage at the reserve. In 1990, the United Nations Environmental Program named Mrs. Merz to its Global 500 Roll. To Mrs. Merz, rhinos — far from being the stupid, aggressive, ill-tempered sorts many suppose — were, in her words, beautiful and elegant. She blamed their bellicosity on their poor eyesight, leading them to charge first and ask questions later. She found that rhinos have a sense of humor and that they communicate by altering their breathing rhythms. She read them Shakespeare to soothe them. Samia, an orphan rhino whom she raised from babyhood, even crawled into bed with Mrs. Merz — not entirely to her delight. Samia would follow her around like a dog, even after leaving Mrs. Merz’s immediate care and returning to the reserve, where she mated and had her own calf. If Mrs. Merz fell, Samia would extend her tail to help her up. Not realizing how big she had grown, Samia once tried to sneak back into the house where she had been nursed and became jammed in the dining room door. Mrs. Merz had to pour a gallon of cooking oil on her rough skin to ease her through.Courtesy: New York Times - April 2013

Go back to: Wildlife guardians & dedicated conservationists

ARTICLES OF INTEREST:

Talking with Anna Mertz by Dale Morris with Africa Geographic 2013 (PDF)

The black rhinos of Lewa by Dale Morris with Africa Geographic 2013

Anna Mertz talking to James Robertson and the Madigan Family 1990