Margarete Trappe

..and the story of Momella (and Hatari)

Margarete Trappe

Margaret Trappe was a German-British wildlife hunter and the first female professional hunter in East Africa. The daughter of the best female aviator of Africa, she made her home in German East Africa in 1907. Her family built their home on the slopes of Mount Meru and named their farm "Momella".

Margarete Trappe and the dream of Africa

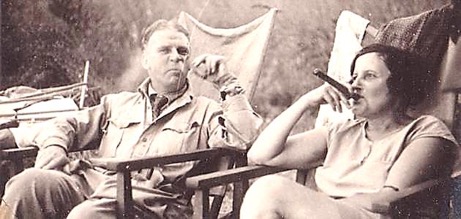

Margarete Trappe was only 23 and freshly married when she emigrated from 1906 with her husband Ulrich from Silesia to what was then German East Africa. They had come by Oxcart with much courage and pioneering spirit from the coast. The trip was certainly not very comfortable, but after they had passed the Meru Pass, the two must have had a spectacular view: Momella, in today's Arusha National Park. Here, in the midst of this beautiful landscape, they built their farm. They owned cattle, goats and horses and also loved the bushland and wildlife of East Africa. "The White Huntress": a legend in East Africa during her lifetime In Silesia, Margarete had learned a lot from a brother-in-law about medicine and medicines. This knowledge combined them with the healing methods of the Maasai and thus helped people and animals on the farm and in the surrounding area. She was an excellent rider and shooter and quickly became known as "The White Huntress". She also enjoyed the highest respect among the Maasai and was called "jejo" (mother) and magic healer. She treated the people, nature and wildlife with much respect and appreciation and hunted only according to certain ethical principles.From the trophy hunt to the film and photo safaris in Tanzania

After the First World War, Margarete Trappe's farm was expropriated - but she returned in 1925 and rebuilt her farm. Since it was almost destitute due to the expropriation, they must finance the reconstruction by trophy hunting with rich European hunting customers. The first professional big game hunter in East Africa was a legend during her lifetime. During World War II the farm was destroyed again. And again, Margarete returned to Momella to rebuild the farm. The protection of the nature and the wild animals stood for them in the foreground in the meantime. Instead of hunting safaris, she now took photo and film safaris.Momella, a place for legends and myths

Margarete Trappe died in 1957. And it is said that during the three days before her death, a herd of elephants stayed at her house. They only disappeared into the woods when Margarete Trappe had died. She was buried at Trappe Farm. The next morning, it is said, her son Rolf had discovered numerous huge prints around the grave there: The elephants had said goodbye.Source: Afrikascout.de

Due to her unusual curriculum vitae, especially as a white woman in an African country, and her fair behavior towards the native Maasai and the animals, she became well known in Tanzania. She was called the "mother of the Maasai" there. After her death, her son Rolf leased the farm to Paramount Pictures as the setting for the classic movie “Hatari”, starring John Wayne and Hardy Krüger. The latter then bought the property in 1960. He wanted a farm in Africa – a dream came true, for 13 years!

Hardy Krüger’s former home was transformed much later into the small and privately managed Ol Donyo Orok Lodge, which closed in 2002. Today this house is part of Hatari Lodge, and is inhabited by the Gabriel family. Jim Mallory’s former house is now the main building of Hatari Lodge. The name was chosen in memory of the classic Hollywood movie “Hatari”, parts of which were filmed in the immediate surrounding areas.MARGARETE TRAPPE'S BIOGRAPHY

by Claudia Diekmann (written on the 60th anniversary of the death of the German-British farmer and first professional big game hunter in East Africa - translated from the original article in German).

"On June 5, 1957, Margarete Trappe died.... bedridden, she had resisted death for three days. During the whole three days there was an elephant herd in front of the house on the edge of the jungle. The lead bull * had approached the window of her death room, except for a few paces. There he stayed until Margarete had died. Only then did he return to the others and lead the herd into the forest. Margarete was buried at Trappe Farm. The next morning Rolf discovered countless prints of huge columns around the grave. The elephant herds had paid a last visit during the night. The freshly raised hill was untouched." Hardy Krüger (* Editor's note: It's more likely to have been a lead cow, elephants are organized matriarchal.)

Not until the hour of her death Margarete Trappe became a legend. Already in her lifetime, the courageous pioneer in a male-dominated world in East African Tanzania was a myth: as a "Jeyo" (mother) and "magic healer" for the local population and above all as a "white huntress". Margarete was the first woman in East Africa to professionally hunt big game and make her living full time. It uniquely designed the popular safaris in the 1920s and 1930s for its paying guests. Margarete loved nature and wildlife in Africa, especially the elephants played a significant role in her extraordinary life. The myth of Margarete Trappe - it continues today in East Africa and beyond the borders of East Africa. It all began on a farm in Silesia at the beginning of August 1884: Margarete Zehe was born here as the youngest of five children. Karl Zehe, who had probably hoped for a second son, taught his daughter riding, shooting and nature and wildlife love and respect. Not exactly the typical education for a girl of this time. Zehe also gave his daughter a longing for the African continent they wanted to travel together. It was the time of the German East Africa colonization: Numerous publications and letters from relatives and friends who had already emigrated awoke the desire to get to know this exotic world. However, it was no longer possible to travel together. The father's unexpected death in 1901 led to the sale of the estate and relocation of the mother and sisters to the nearby small town of Sagan, a development that further enhanced Margarete's courageous desire to emigrate to Africa. One of her earlier goals - a study of veterinary medicine - failed because of social conventions and contemporary legal foundations. This should not happen to her with her emigration to Africa. Therefore, Margarete put the following condition to her future husband, whom she had met in Sagan: Either he agrees to emigrate with her to Africa or she does not marry him. Ulrich Trappe, lieutenant in the "Riding Artillery Regiment" in Sagan, agreed. After exhausting weeks at sea, the couple reached Dar es Salaam on the East African coast at the beginning of 1907. With oxen carts and on foot, they then wandered for weeks through the inhospitable inland, and found some suitable farmland about 600 km from the coast - Ngongongare and Momella. The land was in the paradise-like area around Arusha at the foot of the Meru Pass with a view of Mount Kilimanjaro. The hardships of the past few months had paid off: Margarete was in Africa - her lifelong dream had come true. A lifelong dream she should live beyond any obstacles and until her death. The early years in the new home were characterized by the construction of the farm. The couple lived in the tent for six months, then in a hut made of banana leaves. Four years later, they had built a solid house. Margarete had inherited the money for building the farm from her father. And their work quickly proved successful: The Trappes had a large cattle, processed milk to butter on a large scale, reaped and sold fruit, vegetables and flowers. However, there have also been setbacks for everyday challenges in Africa such as cattle theft, epidemics and diseases. Already in those early years Margarete gained her reputation as "Jeyo" (mother), "magic healer" and "white huntress". In addition to the farm work and their three children (1909 Ursula, 1911 Ulrich, 1913 Rolf), they employed the well-being and medical care of people and animals on the farm and in the surrounding area. Before her emigration, Margarete had learned from her brother-in-law, a doctor, basic medical knowledge and much about important medications. Now she was fascinated by the herbs, rituals, and centuries-old healing methods of the Maasai that she watched and learned. Margarete was passionate about hunting, was an excellent rider and shooter, and was not afraid of big animals. Apparently, she did not even get in the store from her beloved horse Comet. "Even today there are (in Arusha) old people, who report that Mrs. Trappe did not dismount even when she was running errands. She simply rode into the shop, brought the horse to a halt in front of the counter, and delivered her orders from the saddle. "(Hardy Krüger) Such incidents the African people liked to tell around the campfires and in the farmhouses. Margarete brought great respect to the indigenous people, who had already endured much suffering under the German colonization of Africa - a setting that was very unusual for a white man in the colonial era. Trappe hunted only according to certain ethical principles such as "Never shoot from a tree, but give every animal a chance! Never shoot at waterholes, because scooping in the Pori is a sacred act! Never shoot a female animal, let alone a mother animal! Never let go of a wounded animal until it is released from its pain!" The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 changed the life of the Trappe family in Africa considerably, because the armed conflicts in Europe were also fought in East Africa. Ulrich Trappe was drafted into the imperial security forces. Since Momella was in the border area, Margaret wanted to bring their herd with more than 1000 cows, cattle and Zebuvieh before the English soldiers to safety. Her three small children had to leave her under the care of her sister Tine, who had been living on the farm for some time. For three months Trappe then accompanied the German Schutztruppe under the command of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, assisting them with meat and especially with fresh horses, which she boldly maneuvered past the British secret service. A woman in the war zone and one more, which defied the British soldiers: the nickname "Iron Lady" made the rounds fast. When Trappe finally returned to Momella with her children, her farm was destroyed, her savings bankrupted by the British government. Since Margaret had no more money, she now began to earn money with her hunting passion. She hunted and sold animals to order. Even as a poacher she adhered to the ethical principles of her hunt. The British occupiers finally got wind of the matter. They took advantage of Margarete's skills and knowledge, and hired her as a gamekeeper for a fixed salary. This was their money worries for the time being fixed. After the end of World War I Germany lost the African colonies. Exile lasted for five years in Germany, then Margarete and her husband returned to Africa with the help of British passports. Ngongongare was lost, but Momella could be bought back and rebuilt. In 1926 daughter Rosi was born. Around her day of birth, a special legend entwines, which should shape sustainable Margaret's relationship with elephants: During the birth in the tent kept a herd of elephants very close. At the first sound of the newborn Rosi, the elephants lifted their proboscis and trumpeted the baby's crying. From now on, the elephants were allowed to stay on Momella unhindered and eat everything they could find. But even the birth of the daughter could the alienation of the couple by the constant financial problems, the frequent long separations and the war and its consequences do not stop: 1928 the marriage of the Trappes was divorced. A divorced woman - in Europe at the time still a stigma with social consequences - was the least of all problems in Africa and meant for Margarete a next and financially necessary step on her career path. In order to finance her farm and bring her family through, Margarete now led safaris for hunt-hungry Europeans and celebrities. What was special about her safaris was that she passed on her hunting ethics to her clients: Margarete obligated her paying guests to watch the animals respectfully and patiently and not simply go out into the bush and shoot any animal at random. The outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, just like the First World War, had serious consequences for Margarete and her family. The children, all of whom did not have an English passport, and Margaret's sister Tine were soon interned in various camps, including Margarete herself - the English passport was no longer enough to protect her. In February 1943, Margarete returned to Momella. At age sixty, she began rebuilding her run-down farm for the third time. Their household goods and the cattle had been foreclosed, money was again no longer available. But that's not all: after the end of the war, the entire family Trappe should be expelled from the country. Influential English friends were able to avert this renewed stroke of fate. Margarete Trappe was meanwhile no longer interested in leading or hunting big game safaris. Instead, she campaigned even more for the protection of nature and wildlife in Tanzania. Due to her profound knowledge in this field, she now took on orders for photo and film safaris of paying guests. Margaret's son Rolf and his wife Halinka supported her from now on in the management of the farm. So Margarete Trappe lived her dream of Africa until she died on June 5, 1957 at the age of 73 years in her beloved country. Farm Momella became famous in the 60s for the film "Hatari" starring Hardy Krüger and John Wayne. Kruger bought the farm from Rolf Trappe and converted it into a bush hotel. Today the area is part of the Arusha National Park. Some buildings of the farm are now operated again as a hotel. The children and grandchildren Margaretes lived and live partly in their tradition of "white hunter" in East Africa and keep the memory of them alive. The life of Margarete Trappe was filmed in 2007 by ZDF (a cinematic memorial documentary drama Momella - A Farm in Africa.MARGARET'S STORY - Between Two Fires – The African Saga of Margarete Trappe By Fiona Claire Capstick

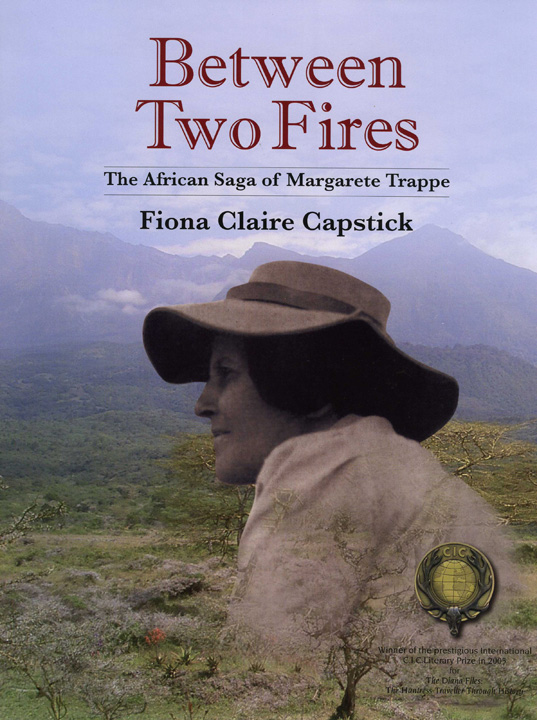

Fiona Capstick sums up Margarete Trappe as,“farmer, equestrienne, livestock breeder, skilled amateur veterinarian, healer of humans, transport rider and intelligence operative during the First World War, formidable first full-time professional game huntress in Africa, photographic and eco-safari leader, and protagonist of goodwill among the tribal people of her African home.”

She was born into a well-to-do family of five children in Petersdorf, Silesia, which was part of Prussian Germany for 200 years until 1945, and today lies in southwest Poland. Margarete was denied the opportunity to study veterinary medicine because of her gender. Instead, the already headstrong and animal-loving young woman set her mind on emigrating to Africa with her husband Ulrich Trappe, a Lieutenant in the Silesian mounted artillery regiment. In 1906, under Chancellor Bismarck’s colonization program that would provide the means to acquire land and the basic necessities to start farming, they embarked on the Deutsch-Ostafrika Linie for the German East Africa. Fiona provides historical background for the reader to understand the European politics behind the acquisition and administration of the almost 1-million km2 Protectorate, surrounded by British, Portuguese and Belgian possessions, as part of Germany’s “Scramble for Africa” that started under Kaiser Wilhelm I. The anchoring of German warships off the Sultanate of Zanzibar; a discussion of Swahili culture; the 1886 Anglo-German treaty of 1886; the devastating end-of-century Rinderpest that killed 90 to 95% of Africa’s cattle and much game; the bloody 1905 Maji Maji rebellion; and even the summiting of Mt. Kilimanjaro by Dr. Hans Meyer on October 6, 1889, are interestingly fleshed out. We follow the Trappe’s 485-km trek with cooks, gunbearers, servants and trackers, from Tanga on the coast to “The Shining Mountain,” and the slow, laborious creation of Ngongongare and Momella farms in the elephant, rhino and buffalo-rich foothills of Mount Meru. We share the tented and banana-leaf house beginnings and the eventual emergence of a magnificent estate with its dairy herds, horse stud and cattle ranching six years later. The photos of the young Margarete on her black stallion, Comet – whose own saga is another story, with Africa’s ancient volcanic mountains in the background, is a page-turning read. Throughout, Fiona provides insight into the period’s agricultural markets, the creation of game reserves for the protection of wildlife, the introduction of hunting ordinances, including the abolishment of ivory hunting for commercial purposes. She describes the character Margarete developed to raise a family and expand their holdings, while facing too many challenges and near defeats as the specter of the First World War builds to its inevitable conclusion for the colony’s 5,336 whites; 4,101 were German. From those early days, Margarete’s reputation as a skilled huntress grew and spread, and she soon earned a request from the Bavarian Royal House of Wittelsbach to organize a safari for Prince Leopard, Field-Marshall of the Imperial Army and son-in-law of Kaiser Franz Josef of Austria, and his son. Her list of aristocratic clients would grow, and Fiona reconstructs many of their safaris from meager surviving documents and letters. Everything would change for the 30-year-old mother of three with the declaration of war. Fiona details the creation of a colonial armed force by the Prussian aristocrat Lt-Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, and his guerilla war strategy throughout the war to defend the German colony. The sinking of the Königsberg; General Smuts; the British assault on Longido – it’s all there. Margarete had her own role to play, as mounted reconnaissance operative, also delivering and treating military horses, all the while looking after her estates, her staff, her children. Ulrich was taken as a prisoner of war to India and it would be years before she saw him again. Lettow-Vorbeck would say she had “Schneid für drei Männer” – the guts/courage of three men. Margarete was never an easy person, but she was fair and square, which earned her the position of Honorary Game Warden under the new British authorities, who had restricted her movements. In 1916, while poaching game to feed her people, she started to rebuild Momella, slowly re-acquiring 600 head of cattle, 50 horses, and 300 sheep and goats. But in 1920, after 13 years of labor, the colony’s 4,000 German nationals were deported to return to their devastated homeland in the throes of economic collapse and revolution. The British confiscated all Margarete’s property, forbidding her to sell anything. But Margarete would find a way back to Momella via the acquisition of a South African passport, and in 1926 she gave birth to her fourth child, and divorced her husband in 1928. These years, until the next war, would be the golden years in many ways – raising the children among lion cubs and pet zebras, rebuilding the farm and re-establishing her safari business stocked with blueblood clients, including Kaiser Wilhelm II’s grandson, Prince Hubertus of Prussia, and Prince Friedrich Franz von Mecklenburg-Schwerin who hunted Lake Manyara and Tarangire. Count Rantzau was Margarete’s first and most enduring client, encouraging her to become a full-time PH – the first in all Africa. Safari life with its freedom and danger suited her nature and encyclopedic knowledge of wildlife, firearms, the field preparation of skins, following spoor with her trackers. Soon her sons Ulrich and Rolf assisted in the family business, while her daughter Ursula married and moved to a sisal plantation in the Lindi region. Fiona recounts the rising pressures in Europe that would cause the inhabitants of Momella to be “sucked into a situation not of their making… This, too, would pass, but at what cost and when?” British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. Despite her South African passport, which made her a British Dominion subject, to the Brits Margarete was an enemy alien. Soon, 4,000 Germans, and most Afrikaner/Boers in Tanganyika, would be interned at Iringa; many men were sent to camps in South Africa and the women and children to Southern Rhodesia. Margarete’s sister, Tine, and her children Ursula, Ulrich and Rolf were all detained and ultimately deported. By 1951, they had all returned except for Ulrich who refused to return to Tanganyika. Margarete, too, was finally interned, somehow managing to keep her two dogs, and Momella was to be auctioned off to the highest bidder. She was eventually allowed monthly visits to the estate where she was confronted by “waste, neglect, and theft,” and the Maasai and their cattle in its pastures. After two years and four months, in early 1943, she was free to start over. But then, again, after years of ceaseless labor, the British arrived at Momella in November 1946 to deport her to a place – Prussian Germany – that no longer existed. Six months later, the order was abruptly withdrawn. With the time for big-game rifles now behind her, Margarete would make a successful business of photographic and film safaris, though Rolf followed her into the game fields through the wind of change. Margarete Trappe died on June 5, 1957. But Momella, as part of Arusha National Park and the Hatari Game Lodge, live on, as does the legacy of an exceptional human being.REMEMBERED

The tombs of Margarete Trappe and her son Rolf are located just outside the Arusha National Park. At the park exit we collect an armed ranger who will accompany us. After a short drive we reach the new farmhouse of Margarete Trappe and from here we continue on foot. The narrow path, usually used by buffaloes, leads down through bushes. We climb over Dikdik Köttel and Henna plants and arrive at a clearing - the favorite place of the Trappes. Irritated, I look at a small round wall in the middle of the wilderness. The ranger explains that this is the swimming pool, which I think is a joke. No, it's no joke - this was actually the swimming pool of the Trappes. In the meantime nature has recaptured him. A few steps further we reach stone slabs embedded in the ground: the graves of Margarete Trappe and her son Rolf. It is a peaceful, quiet place. And I think I feel a touch of history. A touch of bygone days in East Africa. When a woman had a farm in East Africa (Source: Afrikascout.de).

HATARI LODGE - ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK, TANZANIA

Hatari Lodge is situated in a malaria-free altitude, above 5,.000 ft, on the northern edge of Arusha National Park, with its unspoiled views of lakes and craters, its magical rain forests, and the 4,566 metre high dormant volcano Mount Meru, which rises elegantly in the background. At the very heart of this “luxury bush hotel”, managed by Marlies, Jörg and their staff, are the traditional farm buildings, which were used by the legendary actor Hardy Krüger, and his former manager, Jim Mallory. Views from the Hatari terrace and the walkway out onto the seasonal Momella swamp frame all these wonders and spectacles.

The lodge is named after the Hollywood film, 'Hatari!' (meaning 'danger' in Swahili), starring John Wayne and his German co-star Hardy Krüger and fimed in this area in 1960. In Willy's Jeeps and Chevcrolet trucks, the pair raced over the savannah catching rhinos, giraffes and other large mammals, all destined for zoos around the world, portraying an era when capturing wild animals was still big business amongst the tough heroes in Africa. The many months of filming 'Hatari' interrupted Hardy Krüger's new and promising Hollywood career and, as Africa got into his blood, he decided he didn't want to leave. Every free day was spent searching between Mount Kilimanjaro and the Serengeti for a suitable home. A farm known as 'Momella', which he had seen during the filming of 'Hatari' captured his heart. Today his former home and that of manager Jim Mallory form part of Hatari Lodge.Source: Eyes on Africa

ARTICLES OF INTEREST:

Tanzania: Hatari in the Arusha National Park - How the Momella Lodge became famous.

From “MOMELLA an African game paradise” by Maximilian von Rogister (PDF)

Go back to: Leaders in tourism and conservation

.jpg)