Richard Leakey

Wildlife Warrior

Richard Leakey (born December 19 1944)

Anthropologist | Politician | Wildlife conservationist and author

Richard Erskine Leakey was born in Nairobi, Kenya, a grandson of English missionaries. His father and mother, Louis and Mary Leakey, were distinguished paleontologists who had pioneered the archaeological exploration of the Great Rift Valley of East Africa. The second of three brothers, Richard Leakey spent his childhood trailing after his parents on archaeological digs, searching for the fossils of extinct species and human ancestors. He found his first fossil when he was only six — the jaw of an extinct species of giant pig — but he was more interested in tracking living animals in the wild.

In 1959, Mary Leakey discovered the fossilized cranium of an extinct hominid, Zinjanthropus, in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. The discovery of a human ancestor of unprecedented antiquity focused the anthropological community’s attention on Africa as the cradle of mankind and brought the Leakey family international renown. But at 16, Richard Leakey wanted no part of squatting under the African sun, scratching the dirt for fossils. He dropped out of school and struck out on his own. He trapped animals and collected skeletons for research institutions, learned to fly, and started a business taking tourists on photographic safaris.

While still in his teens, he joined a former colleague of his parents on a fossil-hunting expedition to Lake Natron on the Kenya-Tanzania border. To his surprise, he enjoyed the venture, but lacking academic credentials, he received little credit for the team’s discoveries, so in 1965 he traveled to England to catch up on his schoolwork, with the intention of resuming his education. When this proved more difficult than expected, he returned to Kenya, where he managed paleontological expeditions and worked for the National Museum of Kenya. In 1967, he joined a successful expedition to the Omo Valley in Ethiopia. On a flight between Omo and Nairobi, he spotted an expanse of sedimentary rock on the shores of Lake Turkana, formerly known as Lake Rudolf. Leakey suspected the area was rich with fossils. When a return trip confirmed his hunch, he secured funding from the National Geographic Society to run his own excavation. With a crew of Kenyan fossil hunters who called themselves the Hominid Gang, he uncovered a rich vein of artifacts that startled the world. After years in his family’s shadow, Richard Leakey had earned a reputation as an outstanding fossil hunter in his own right.

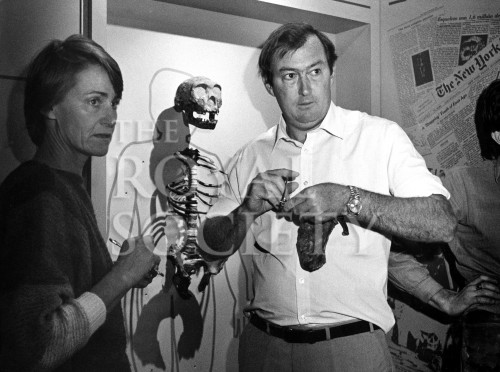

In 1968, at the age of 25, he won appointment as director of the National Museum of Kenya. Within a year, he was diagnosed with a terminal kidney disease and told he only had ten years to live. In spite of this diagnosis, he forged ahead with his life. He married zoologist Meave Epps, a primate specialist who had worked with his father at Tigoni Primate Research Center. As director of the Museum, Leakey undertook intensive excavation at Lake Turkana. Over the next 30 years, the site yielded more than 200 fossils, including two of the most spectacular finds of all time, a virtually complete Homo habilis skull in 1972 and a Homo erectus skull in 1975.

By the end of the decade, Leakey’s kidney disease had grown severe, and he traveled to London to consult a specialist. He received a transplant from his younger brother, Philip, but within a month, rejection set in. The drugs that suppressed the rejection weakened his immune system, and he nearly died from an inflammation of the lungs. Leakey survived, recovered, and returned to Kenya. In the eight months he had spent abroad, he wrote an autobiography, One Life, although the most dramatic chapters of his life were yet to come.

In 1984, his team found one of the most historic specimens of all, the nearly complete skeleton of a young male Homo erectus. The 1.6-million-year-old skeleton, nicknamed Turkana Boy, is one of the most complete hominid fossil skeletons ever found. Leakey described this discovery and its significance in the book Origins Reconsidered (1992). In 1985, the site produced the skull of a previously unknown species of extinct hominid, Australopithecus aethiopicus.In nearly 30 years as director of the National Museum, Richard Leakey had built the institution into a major international research center. In 1989, he accepted an appointment by Kenya’s president, Daniel Arap Moi, to serve as director of the Kenya Wildlife Service. As director he was called on to rescue the country’s chaotic park system and combat an epidemic of rhinoceros and elephant poaching. The illegal demand for the tusks of these endangered animals was pushing both species to the brink of extinction. Leakey created well-armed anti-poaching units, and when gentler measures failed, ordered the shooting of poachers. In 1989, Leakey staged a dramatic burning of 12 tons of confiscated tusks. The elephant population was soon stabilized and is now growing. Impressed with Leakey’s achievement, the World Bank approved substantial grants to the Wildlife Service.

Although Leakey’s accomplishments won international recognition, he had made enemies at home. In 1993, his plane suffered an unexplained equipment failure and crashed in the mountains outside Nairobi. The accident cost Leakey both his legs. An expert pilot, he had good reason to suspect sabotage by political enemies. Undeterred, Leakey returned to work, but political opposition forced his resignation in 1994. He recounted the experience in the book Wildlife Wars: My Battle to Save Kenya’s Elephants (2001).Long impatient with the corruption and inefficiency of Kenya’s one-party government, Leakey and other dissidents founded the Safina party in 1995. For two years, the government withheld legal recognition of the party. Government supporters subjected Leakey to public humiliation, death threats and constant surveillance, and finally attacked him with whips outside the courthouse, but Richard Leakey could not be intimidated.

As Secretary General of Safina, he won a seat in his country’s parliament, where he negotiated constitutional reform and introduced laws protecting the disabled. In 1999, international lending institutions cut off aid to Kenya because of rampant corruption in government. Leakey’s sometime adversary, President Moi, asked Leakey to join the administration as Cabinet Secretary and head of the Public Service, with a mission to restore the integrity of the civil administration. Leakey soon earned the confidence of international donor institutions, and lending to Kenya resumed.After retiring from government in 2001, Richard Leakey served as a leading spokesman for Transparency International, a global coalition to fight corruption, and for the Great Apes Survival Project, a United Nations effort to defend mankind’s closest relatives. His books include The Origin of Humankind (1994) and The Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Mankind (1995). His wife, Meave Leakey, and his daughter, Louise, carried on the family mission of searching for the evidence of human origins in Africa, while Richard Leakey continued his work as a highly public advocate for the disabled and for Kenya’s kidney patients.

By 2015, the poaching of wildlife that Richard Leakey had done so much to stop in the 1990s had returned to crisis levels. President Uhuru Kenytatta asked Richard Leakey to return to the Kenya Wildlife Service as chairman. At age 70, Richard Leakey took up the challenge, continuing his lifelong service to the environment and to the continent that gave birth to the human race.Courtesey: Academy of Achievement

ARTICLES OF INTEREST

Saving Africa's Natural Treasures Washington, D.C. June 21, 2007

Ivory and Corruption: An Interview with Dr Richard Leakey by Jan Fox August 2013