RUPERT FOTHERGILL

THE HERO OF OPERATION NOAH - LAKE KARIBA

Rupert Fothergill

Game Warden | Leader | Conservationist

Then, as now, the Zambezi Valley which forms the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe (then Northern and Southern Rhodesia) was one of the richest wildlife sanctuaries on the planet. Rhodesia’s Chief Game Ranger was Rupert Fothergill. In 1958, he was tasked with rescuing the Kariba wildlife. Over the course of the next five years, until 1964, he, his team and volunteers worked under the most rigorous conditions, living in basic bush camps, often travelling in rowing boats, using equipment no more sophisticated than ropes, sacks, nets (made of old nylon stockings), boxes and dart guns. The men rescued and relocated over 5000 animals, from zebra and warthogs to snakes, rhino and elephant, lion and leopard, most of which were taken to the Matusadona National Park. Tad Edelman headed up a second Northern Rhodesian team which saved another 1,000 animals. Nothing like it had ever been attempted before and it was an astonishing feat.

ABOUT OPERATION NOAH

The dam wall of Lake Kariba is located at the former Kriwa (Kariba) gorge and stands 128 m (420 ft) tall and 579 m (1,900 ft) long. It is a concrete double curvature arch dam, of mass concrete construction reinforced around the spillway gates and took four years to complete. Kariba dam was designed for the safe passage of a 10 000 year flood, based on river flow data available at the time.

The Kariba South Bank Power Station of the Kariba Dam hydroelectric scheme was officially opened by her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother on 17th May, 1960.Following the wall's contruction, Kariba’s rising waters put the lives of thousands of animals in danger prompting the most extensive and courageous rescue operation ever undertaken, aptly named Operation Noah.

As the dam wall closed and the waters rose, milliards of large crickets, mice, rats, and the like emerged and scurried away from the encroaching waters. The skies above were blackened by swarms of birds sating themselves on the harvest. In the water the voracious tiger fish rampaged and, glutted with drowning insects, died. Many animals, notably the larger carnivores, retreated inland. Others, however, instinctively made for high ground to wait out another seasonal flood, and were trapped on temporary islands created by the unrelenting upsurge as Lake Kariba filled.According to the local baTonga people, the Zambezi river god, the great snake, Nyaminyami, had now withdrawn from the world of men in anger and despair. The dam across the Kariba Gorge had separated him from his wife. He had shown his wrath during the building, visiting floods and death on the workers but nothing had stopped the machines and now and he was waiting for the moment when he could destroy the dam and be reunited with his love.

As for the baTonga, 57,000 people were being forcibly resettled as the waters of the mighty Zambezi river slowly backed up against the wall to create the world’s largest artificial lake, a staggering 223 kms (140 miles) long, up to 40 kms (20 miles) wide and covering an area of 5,580 sq kms (2,150 sq miles). The people might have been safe but it was fast becoming clear that many thousands of animals were about to perish as they sought refuge on islands that were shrinking and sinking under the rising waters. And so Operation Noah was born.

Senior ranger Rupert Fothergill, Brian Hughes (an ex-fireman who could not swim) and their assistants arrived. Under-manned and under-equipped, Operation Noah had begun.

Larger animals such as buffalo, elephants and those that could swim made it to safety on the Matusadona mainland to the south of the growing lake. But many didn't. Rupert Fothergill moved quickly to address the plight of those animals that remained marooned on the temporary islands.

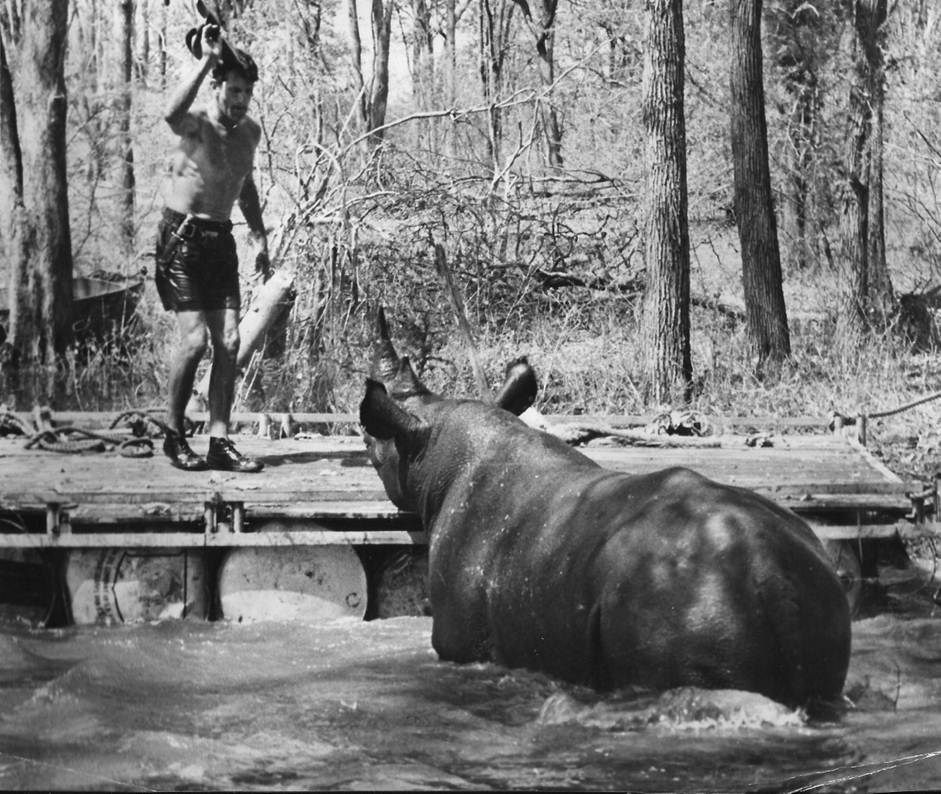

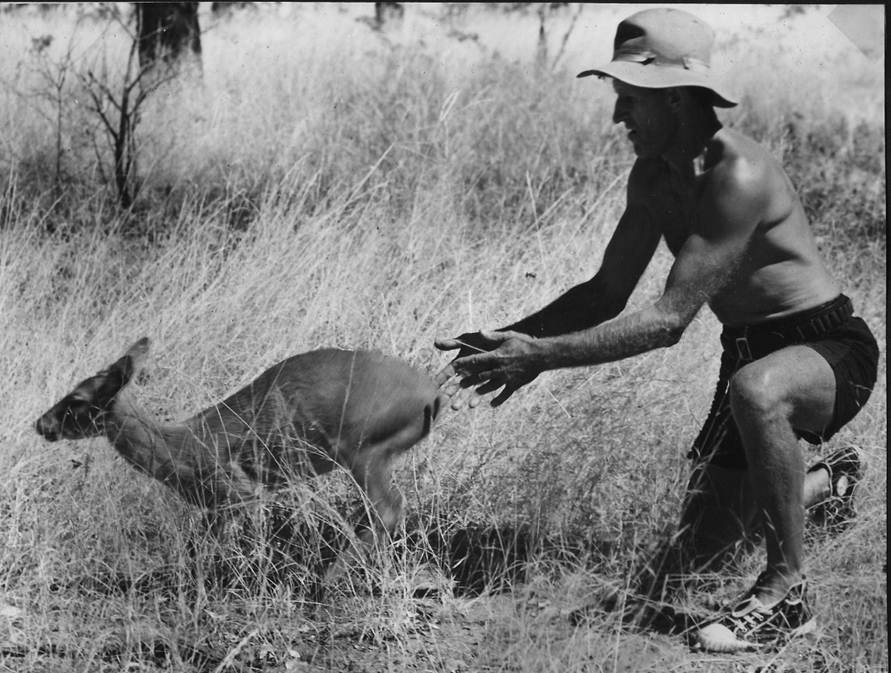

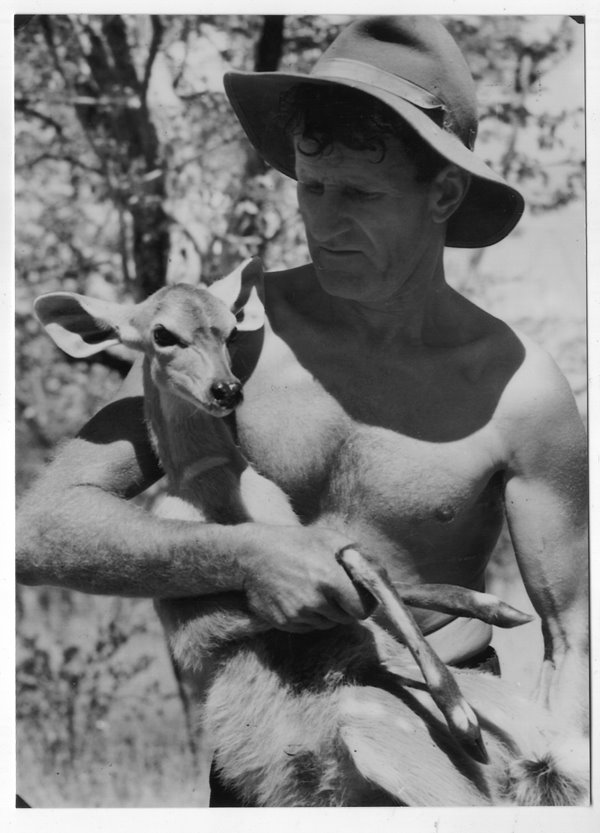

They embarked on an extensive exercise to evacuate the stranded animals, using various methods which included tying them up and transporting them by boats. The methods evolved over time. At some stage, they famously resorted to using women’s nylon stockings as these were friendlier to the animal hides than rope. Where necessary, they also used darting and tranquilizing. Unfortunately, some animals did drown during the historic rescue exercise. Notable amongst the ‘beneficiaries’ of Rupert Fothergill heroics were elephants, black rhinos, kudu, hare, zebra monkeys, snakes and even porcupines! (pictured). As much as possible, the rescue team saved every type of animal, irrespective of size or any other consideration. This mission served to set the foundation of the present day Matusadona Game Reserve, now a National Park and home to a wide and rich variety of African wildlife.

They were able to manoeuvre the large animals into the water and sheperd them to safety. In so doing, it was revealed that many mammals could swim long distances – waterbuck a full mile and baboon 400 yards, for instance. They also discovered that hornless female buck could paddle further than the males. And they observed instances of intelligent, adaptive behaviour such as waterbuck ferrying offspring on their backs and large horned bull antelope supporting their heads on logs, or testing them on others’ backs, during their journey to safety. Others, declining the swim, were driven into the water for easier capture before being trussed and transported to shore. During this time tranquilliser darting techniques were pioneered. This was a heroic period, when a handful of men drove themselves to the verge of collapse whilst their gains were pathetically small as thousands of animals drowned or died from shock or injuries sustained during the rescue operations.Through the British Sunday Mail (February 15 1959) the story of Operation Noah fired the sentimental imagination of the world. Soon there were more feature writers, television cameramen, do-gooders, and inquisitive officials than there were designated rescuers and their intrusion severely hampered operations. A request for and nylon stockings to plait as replacements for the ropes which burnt captured animals, saw millions of pairs inundate the locals SPCA in another unstoppable flood.

Provoked by pressures of a press-fed public and humanitarian organisations, the task force was increased and better equipped by the Southern Rhodesia government. Overseas financial aid was refused, however, because of the danger of donors deeming it their right to intervene in the project. These funds were diverted to Northern Rhodesia (Now Zambia) and used to launch their participation in the rescue campaign. Operation Noah, the largest animal rescue ever undertaken, saved over 5000 animals, including 50 black rhino between 1960 and 62. How many creatures died will never be known. Ironically, in the 12 years up till then, over 300 000 animals had been killed as part of the programme to control the spread of Tsetsi fly in Southern Rhodesia.Fothergill also found time to document the rescue on 16mm. Some of it was cut together by the Rhodesian government. I remember watching it at the movies as a little girl. But most of it never saw the light of day.

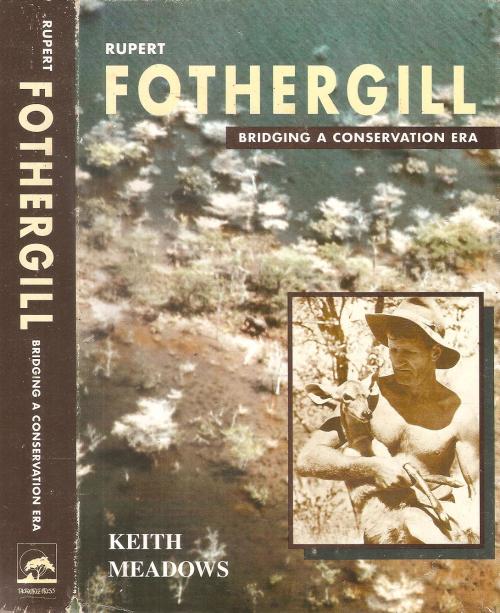

“I never met my maternal grandfather,” recalled his granddaughter Kirsten. “He died ten years before I was born. But I grew up watching him chase rhinos, nurse baby kudu, hold eight-foot pythons and coax porcupines out of their burrows. For almost half a century, his footage of charging rhinos, drowning monkeys, netted antelope and caged lions sat in boxes in our family home. Mum and Dad used to dig out the four half-hour episodes edited by the Rhodesian government and project them at our childhood birthday parties, or invite the neighbors over for screenings in the garage on rainy Sunday afternoons. But the bulk of the raw footage has not been seen for almost fifty years.” Thanks to Kirsten, some of it is now on YouTube (see Operation Noah on Memories of Rhodesia, Operation Noah part (1) and Operation Noah part (2) and there are a couple of books on the subject, a biography, Rupert Fothergill; Bridging a Conservation Era, by Keith Meadows (1996) and a book about Operation Noah, Animal Dunkirk, by Eric Robbins, but both are hard to find. However, this heroic first, that led the way for translocation programmes across the globe, should be far more celebrated than it has been.Courtesy: MV Matusadonna and Malissa Shales

CONTEMPORARIES

Tom Orford was a friend and contemporary of Rupert Fothergill and was involved with Operation Noah, being one of the first recruits to the game department. He also started Kyle National Park and brought the first white rhinos into Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). His son, Bryan Orford, has written a book about his life, called Kamchacha, and available on Amazon.

PUBLICATIONS

A number of books have been written about Operation Noah and Rupert Fothergill's team of rescuers:

Rupert Fothergill - bridging a conservation era by Keith Meadows

Animal Dunkirk - Kariba Dam by Eric Robins & Ronald Legge

Kariba - the struggle with the River Gods by Frank Clements

Go back to: Early conservationists

REMEMBERANCE

In recognition of his exploits, a plaque was erected in Rupert Fothergill’s honour by ex-Park warden and veteran professional guide, John Stevens. Appropriately located in the Matusadona Mountains, it overlooks the lake and valley floor – a fitting tribute to his conservationist cause.

An island on the lake was also named in his honour.