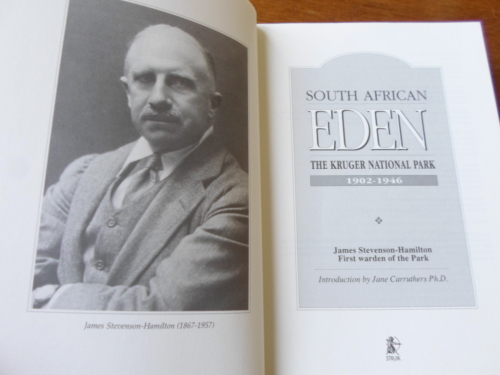

James Stevenson-Hamilton

First warden and protector of the Kruger National Park

James Stevenson-Hamilton

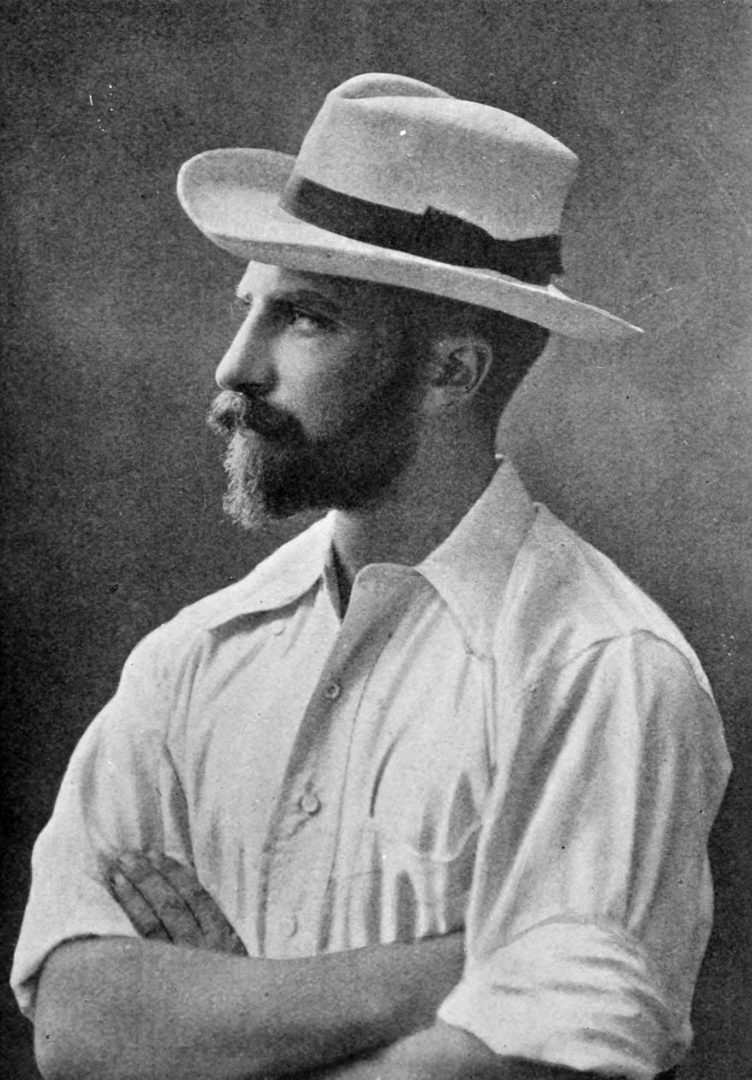

JAMES STEVENSON-HAMILTON was born in Dublin, Ireland, of Scottish parents, in 1867, where his father was then posted. His childhood was spent at the ancestral home Fairholm, in Scotland, and was educated at Rugby School. He proceeded to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and obtained a commission with the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, then in South Africa.

He was on active service with his regiment in the South African War (1899-1902), at the end of which he was offered the wardenship of the Sabi Game Reserve by the Milner Government of the Transvaal. He obtained a two-year leave of absence from his regiment to begin the great task of saving the remnants of the once great herds of game left by hunters and soldiers of both sides fighting in the war. He became involved in the welfare of his animal charges to such an extent that he stayed for more than forty four years until his retirement in 1946. The continued existence and development of the Kruger National Park is largely due to his dedication and sound administration.The reserve was in a sorry state and the balance of nature was seriously impaired, especially as regards the larger mammals, and game laws virtually existed on paper only. Giraffe, hippo, buffalo and rhino were extremely rare, elephants occasionally wandered in from Mozambique but did not stay at first, and other species were scarce and very wild.

At Komatipoort, he was fortunate enough to engage Rupert Atmore, Harry Wolhuter and also several Black assistants before proceeding to Sabi Bridge in November 1902 which was to be his permanent headquarters.So started his labour of love, involving the patience of Job and careful diplomacy, for he had neither the funds nor the authority to make haste other than exceedingly slowly. Stevenson-Hamilton was given very vague instructions, the only one he remembered clearly was ‘to make himself as unpopular as possible’ amongst the hunters and poachers. One of his first operations was to evict all people other than those required for service in the maintenance of the reserve. For this reason he earned the name ‘ Skukuza’, which means: ‘he who sweeps clean’.

This brought him into conflict with various Native Commissioners. He consequently had to rely on persuasion after personal contact, which necessitated many wearisome journeys. Finally he decided to travel to Pretoria and Johannesburg to seek approval and legislation for a set of regulations confirming judicial powers on the Warden of the Reserve. These were ultimately approved and he became Native Commissioner, Customs Official and Justice of the Peace for the territory and appointed rangers to help him in his task.

It was not long before Stevenson-Hamilton realised that the boundaries of the Sabi Game Reserve, defined roughly by the land between the Sabie and Crocodile Rivers, the Lebombo Mountains and the Nsikazi River to the west, were too confined. He decided, on his own initiative, to call on the manager of every land-company owning property north of the Sabie River. A Mr Pott was responsible for effecting the introduction to most of the other managers and advising the modus operandi for approaching each individual, in order to obtain a sympathetic hearing.

Eventually these companies agreed to the safeguarding by the Reserve staff of the fauna and flora on their properties in exchange for the collection of rents and taxes and general supervision for a period of five years.

In 1904 the Sabi Game Reserve extended from the Crocodile to the Olifants River and to this was added a new area between the Letaba and the Limpopo called the Shingwedzi Reserve, excluding a strip of’ foreign territory which was proclaimed mining area between the Olifants and the Letaba. The area under control now comprised nearly 14 000 square miles and was guarded by a staff of five White and fifty Black rangers.The rangers were Maj James Stevenson-Hamilton at Sabi Bridge (Skukuza), Harry Wolhuter at Pretoriuskop, C R de Laporte at Crocodile Bridge, T Duke at Lower Sabie and Major A A Fraser at Malunzana, Shingwedzi.

There was no ranger available for patrolling the area between the Sabie and Olifants River, so the Warden decided to prune expenditure by reducing his own salary and curtailing the transport and climatic allowances of the staff, and thus provided sufficient money to employ G R (Tim) Healy for this purpose. The animal population gradually expanded, slowly at first but nevertheless steadily. To encourage this expansion and to assist the balance of nature, the Warden and rangers shot lions, wild dogs and crocodiles. Herds of antelope began to be seen in place of single animals.During the Great War of 1914-1918 Stevenson-Hamilton left to serve in the Imperial Forces. During his absence a Commission was appointed to investigate the desirability of reducing the areas of the Sabi and Shingwedzi Reserves.

For many years there had been agitation by Lowvelders, farmers for the most part, that the Game Reserve was a waste of time; that it occupied marvellous farming land; that it harboured disease for stock such as East Coast Fever, foot-and-mouth, etc.But the Commission, after inspecting in loco, was convinced that the whole area was a sound one and recommended that the Reserve’s status should be raised to that of a National Park.

In 1919 three new rangers were appointed: P L (Piet) de Jager, J J (Kat) Coetzer and W W Lloyd. Coetzer was placed at a new station north of Shingwedzi near the Pafuri River, which he called ‘Punda Maria’.Coetzer was an ex-soldier and had served in East Africa, where he had come across the Swahili word for a zebra, Punda Miliya, or striped donkey. He had thought that the last word was Maria, his wife’s name, and thus christened his new home in her honour.

The years 1921 and 1922 were difficult and dangerous ones for the Reserve. A coal syndicate, backed by political influence, had secured a concession to prospect north of Crocodile Bridge, the Railway Administration was advocating the sale of farms within the Reserve to make the Selati Line pay.Winter grazers (having secured rights in the buffer area of Pretoriuskop) were all for a deeper penetration into the Reserve and farmers just south of the Crocodile River were clamouring for land on the north bank. Various minor newspapers attacked the expenditure of the taxpayers’ money and alleged that the Game Reserve was a harbour for dangerous animals and a focus for disease.

The attitude of the Government began to veer in favour of what appeared to be public opinion and Stevenson-Hamilton became alarmed. In 1923, at a meeting in Pretoria, several Government Departments claimed the land occupied by the Sabi Game Reserve.However, opportunely as it happened, the SA Railways began its ‘Round-in-nine’ service and a night’s stop-over with camp-fires was arranged at Sabi Bridge. The passengers declared this the most exciting and interesting episode of the whole tour, and immediately the Game Reserve began to be recognised for the tourist attraction that it was.

Col. Deneys Reitz became an enthusiastic advocate of the National Park scheme and so did various other prominent personalities such as Sir William Hoy, the General Manager of the Railways, who requested Stratford Caldecott, an artist, to be the Railways publicity agent for the advertisement of the Sabi Game Reserve as a potential asset. Caldecott was also an enthusiastic writer and after spending two months in the Reserve, his influence in South Africa was such that soon there was hardly a man, woman or child in the country who had not heard, or read, or seen pictured some aspect of the Sabi Game Reserve.After a change in the government in 1924, which for a time had cancelled all his efforts, he finally won the confidence and support of the Minister of Lands in the new government, P J Grobler, a grand-nephew of President Kruger.

His efforts were crowned with success when, on 31 May 1926, the National Parks Act was adopted unanimously, adding many hectares of land north of the Sabie River to the old Sabi Game Reserve, which was henceforth known as the Kruger National Park in honour of President S J P Kruger who had done so much for wildlife conservation in South Africa. Important enthusiasts who had done most to assist in the passing of the Bill were Col Deneys Reitz, H B Papenfus KC, Oswald Pirow, Gen Jan Smuts and Dr A A Schoch.

The struggle to achieve recognition for his beloved “Cinderella” was over for Stevenson-Hamilton and the reaction set in. In terms of the Act the existing staff would be retrenched from the Government Service and new appointments made, and he considered resigning even if his appointment was renewed.But he was sent for by Piet Grobler, who had very kind things to say about his service and who urged him to continue as Warden, which he was thankful to do. All the staff was re-employed.

The first three cars entered the Park over a road prepared by Harry Wolhuter in 1927. In 1928 the number was 180 vehicles and in 1929, when it was possible to travel as far as the Olifants River, 850 came. There was nowhere to put people up and the rangers were obliged to give up their homes and sleep wherever they could outside.They were also obliged to forsake their normal section duties in order to check permits, answer questions, supply petrol, etc. A rapid building programme was initiated by the Parks Board and by 1930 the Park had constructed 100 concrete rondavels in six camps and obtained additional personnel.

Stevenson-Hamilton was always concerned that the Park should never lose its character and become a glorified zoological garden.The old-timers complain that things are not the same, but for most a visit to the Park is a very rare enjoyment and a pleasure that no South African should miss.

Retirement came in 1946, when he and his wife settled on his farm Gibraltar, adjacent to Longmere Dam, north-east of White River, where he died on 10 December 1957, at the age of 90. He married Miss Hilda Cholmondeley in 1930 and they had three children, Margaret (1931), Jamie (1933) and Anne (1935). Margaret died at the age of 4 years. Hilda died 10 January 1979 and their ashes were left to the wind on 10 April 1979 by their daughter, Mrs Anne Doyle, of England, near Shirimantanga, 12 km south of Skukuza, in their beloved Kruger National Park.Courtesey: A Short Biography of Col. James Stevenson-Hamilton, First Chief Warden of Kruger National Park by John Theunissen (gleaned from “Lowveld Pioneers” by Hans Bornman and from other sources.)

Go back to: Pioneers & Early conservationists

EARLY DAYS

At the end of the Anglo-Boer, the Sabi Game Reserve (now the Kruger Park), had already been established and was under the guardianship of a new commissioner, Sir Godfrey Lagden. And he was looking for someone to run the park. It would seem that it was fate that Stevenson-Hamilton met the commissioner, and on the 1st of July 1902, Stevenson-Hamilton took up the position of the “head ranger” of the park.

He had never been to the Lowveld, it was his first time travelling to this part of the world. And he was expected to perform the massive task of keeping the park going. His adventurous nature meant he was more than up to the challenges that he would face. He was instructed to go to the park and “make yourself thoroughly disagreeable with everyone”. Of course, not every person living in the area shared Paul Kruger’s conservation dreams. Many would have preferred to take the land, rid it of wildlife and turn it into farmland.

With a wagon drawn by 6 oxen, and the assistance of 3 horses and 3 helpers, Stevenson-Hamilton headed to Lydenburg and then onto Komatipoort. Once he had arrived at the park, his first duty was to recruit men to assist him in turning a piece of conserved land into a game reserve. After spending some time living in the park, he came to the realisation that people and wild animals would not be able to live together. For the sake of the safety of the animals and people alike, he moved the people out of the conserved areas. He did not simply kick them out. Those who left were exempted from paying tax for a year and they were given special permission to travel certain routes in the park, should they have a needed to pass through the park.

Stevenson-Hamilton certainly had his work cut out for him, and he set up his headquarters at Sabie Bridge. He worked with numerous interesting, nature-loving enthusiasts, including Harry Wolhuter, and continued on his mission to protect animals while developing the park.SOME FURTHER DETAIL ON THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PARK

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, commonly known as Paul Kruger, was the President of the South African Republic from 1883 to 1902. It was he who first pleaded “for setting aside certain areas where game could be protected and where nature could remain unspoilt as the Creator made it.” His vision, however, was not shared by other members of his parliament; his efforts to conserve land, especially in the areas between Swaziland and Zululand and in the Zoutpansberg area, met with strong opposition.

In 1891, Kruger managed to amend existing game laws, and the state started providing protection for some animal species. After managing to declare other smaller areas as game reserves, on 26 March 1898, he proclaimed the ‘Goewerments Wildtuin’ (Government’s Reserve) between the Sabi and Crocodile rivers as the Sabi Nature Reserve. After the end of the Anglo-Boer War (1902) and the death of Paul Kruger (1904), the reserve had almost been forgotten until Lord Milner re-issued the proclamation for the reserve. In 1902, Sir Godfrey Lagden, the newly appointed Commissioner for Native Affairs in South-Africa, appointed James Stevenson-Hamilton as the first warden of the Sabi Nature Reserve. As a "bachelor, a man of means and a professional soldier," Lagden deemed him fit for the job even though the post was viewed as unusual and unheard of. Stevenson-Hamilton signed a two-year contract as warden, found a map of the area and set off with a wagon, oxen, provisions and ammunition for an uncharted and malaria-filled land described to him as the "white man’s grave". Game-ranging was still a new term and this allowed Stevenson-Hamilton to have free rein over the Sabi Nature Reserve, his only order from Lagden being "to make himself generally disagreeable" and to try to eliminate poaching. In 1902, he reached Nelspruit. His first order of business was to announce that no shooting was to be allowed and that if he and his servant could live on tinned meat, so could the white men and natives who were inclined to shoot an impala whenever they felt the need. He believed "that if there were no shooting, if animals were left to live in the veld as they had lived before man came on the scene, they would lose their fear of human beings and flock to an area that had once been described as ‘red with impala’". He then moved his headquarters from Crocodile-Bridge to Sabi-Bridge and appointed two rangers, including Harry Wolhuter, and together they trained native rangers. Poachers soon realised that he was serious about the "no shooting" rule, and many were caught, "including, on one occasion a party of senior policemen" who were caught killing a giraffe and a wildebeest and were convicted and fined for their crimes. After this, "what he did is now a matter of history. He trained his rangers, thinned out the lions and the wild dogs, declared war on the poachers and patrolled the whole area." He also became the magistrate, customs collector and border guard, as well as watcher of the railway line to the south of the reserve. His focus then went back to Johannesburg and Pretoria where he started to convince companies in the vicinity to lend him land, eventually giving him a huge block in a remote corner of Transvaal. By doing this, he created the space that is known today as Kruger National Park. Extending the reserve from the original 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2) to 14,000 square miles (36,000 km2). In this larger protected area, wildlife could roam freely from the Crocodile River to the Limpopo River. In 1912, he first presented his idea for the nationalization of the reserve to then Minister of Foreign Affairs Jan Smuts. The idea was to transform the reserve into a national park, but to do this he needed "the support of the public, but to gain that support visitors should be allowed into the park". Unfortunately, World War I temporarily halted these events. In 1926, Piet Grobler established the National Parks Bill in parliament as encouraged by Stevenson-Hamilton and presented Kruger National Park as a realization of the dreams of Paul Kruger. The Sabi Nature Reserve was officially renamed to Kruger National Park of South Africa. In 1927, the park was opened to the public.MANAGEMENT STYLE

In the early years Stevenson-Hamilton was not sure of what was expected of him and when he enquired as much from his superior, Sir Godfrey Lagden, he was famously told to 'go down there and make yourself thoroughly disagreeable to everyone!'

For the first few months, Stevenson-Hamilton stayed at Crocodile Bridge. Then he moved to Sabie Bridge where he had his headquarters. He thoroughly explored his domain and appointed the first game wardens, black and white. That Stevenson-Hamilton took his job seriously was emphasised when he had two police officers, who had poached game, arrested and convicted. This incident earned him quite a reputation. In 1903, he managed to stop the movement of cattle through the park. He also managed to stop all prospecting for coal and minerals. With the proclamation of the Singwidzi Game Reserve in May 1903, Stevenson-Hamilton took over the management there as well. In 1914, the First World War started and Stevenson-Hamilton joined the forces in the north. He left the administration of the reserves to Ranger Cecil Richard de Laporte and after that to Major A A Fraser. Upon his return in 1920, he found everything in a shambles. Fraser had let the administration slip into a mess. Further concerns surrounded the fact that the war had stimulated development and greedy eyes looked at the reserves for agricultural ground. Stevenson-Hamilton fought on every front to save the reserves. Instrumental in helping him was the establishment of the Selati Railway Line, which was originally built to transport gold. However, the gold reserves soon began to dwindle and in 1922, in an attempt to increase the profit of the railroads, the Round in Nine Tour was established. This was a 9-day tour of Mozambique and the Lowveld and included a one-night stop at what is present day Skukuza, and the idea of allowing people into the reserve was born. Stevenson-Hamilton got members of the Provincial Council to visit the reserve on one of these tours and they left with a better understanding of the possibilities of a national park.A LEGACY - Skukuza Camp & Stevenson-Hamilton Library

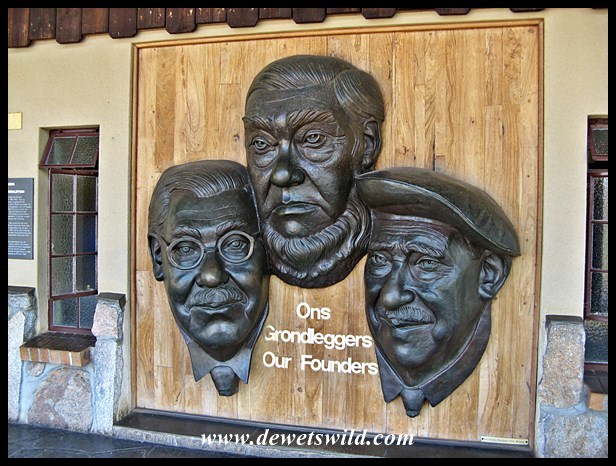

Stevenson-Hamilton was a good friend and fellow of the Tsonga people and he was dubbed "Skukuza" by the Tsonga who lived on the reserve, meaning ‘the man who has turned everything upside down’ or ‘the man who swept clean’. This refers to his efforts to eliminate poaching in the reserve and may also refer to the Tsonga people’s attitude toward him after he had evicted them out of what had been their territory. Stevenson-Hamilton understood Tsonga language as well as Tsonga culture and was taught hunting skills by the Tsonga, who were expert in hunting big game, such as Elephants, Rhino, Leopard and Lion. Skukuza, the main camp in the park and which was formerly called Sabi Bridge, was renamed in honour of him. After his death, "the old men of the kraals, some of whom he had sent to prison for poaching, said: ‘A great man has gone’". A bronze statue created by the artist Phil Minnaar can be seen in Skukuza depicting Paul Kruger, Piet Grobler and Stevenson-Hamilton, the founding fathers of the park. The Stevenson-Hamilton library is also situated in Skukuza camp.Go back to: Pioneers & Early conservationists

PUBLICATIONS

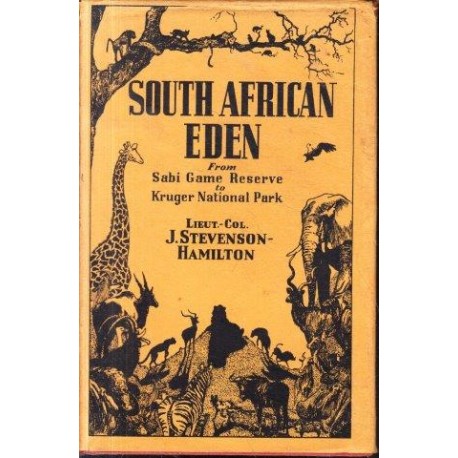

His legacy also lives on in a books that he authored, namely:

• Notes On A Journey Through Portuguese East Africa: From Ibo To Lake Nyasa (1909) • Animal Life in Africa (1912) – foreword by Theodore Roosevelt • The Low-Veld: Its Wildlife and Its People (1929) • The Kruger National Park (1932) • South African Eden: From Sabi Game Reserve To Kruger National Park (1937) • Our South African National Parks (1940) • Wild Life in South Africa (1947) • The Barotseland Journal of James Stevenson-Hamilton, 1898-1899 (1953) Stevenson-Hamilton is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of African gecko, Lygodactylus stevensoni.Courtesey: Wikipedia.org

ARTICLES OF INTEREST

Quote from Shaping Kruger by Mitch Reardon:

Sabi Game Reserve’s first official permanent game warden set up camp in 1902, and for a man in love with wilderness it was a grand place to be and a grand existence. James Stevenson-Hamilton was 35 years old at the time, a tough-minded British ex-cavalry officer and aristocrat from the landed gentry. Before long he would become a ferocious guardian of this wild place. Like the African world came to inhabit, Stevenson-Hamilton was filled with complexities and ambiguities. He evinced inner emotional intensity and outward formal coolness tending to aloofness. He admired order and discipline and could be a martinet; the black subsistence farmers from the Sabi Game Reserve gave him the African name Skukuza, ‘he who sweeps clean’, which should not be mistaken for a compliment. Though short in stature, he conveyed the impression of contained power with a larger-than-life persona. His vision, ambition and impatience of others who did not share his view garnered him as many critics as it did admirers. Yet there was something almost poignant in Stevenson-Hamilton’s avidity for his cause. He was an environmentalist before his time, one of those solitary, pioneering naturalists who have all but vanished into history.

Go back to: Pioneers & Early conservationists