Ted Reilly

Conservation legend of Eswatini (Swaziland)

Ted Reilly

From nothing, Swaziland now boasts several formal protected areas, including Mlilwane Wildlife Sanctuary (4600 ha), Hlane Royal National Park (25 000ha) and Mkhaya Game Reserve (10 000 ha) - this is Ted Reilly's legacy.

After spending a few days with Ted Reilly, I was struck by how much he loves Swaziland and its natural heritage, including all wild animals. He is an inspirational person. Scott Ramsay (photographer and writer)

THE EARLY YEARS (courtesey: Feral Jundi.com)

James Weighton Reilly (nicknamed Mickey), Ted Reilly’s father, settled at Mlilwane in Swaziland in 1906 – this name, meaning ‘little fire’, being derived from the numerous fires started by lightning strikes on Mlilwane hill. It was here that Mickey Reilly constructed the quaintly colonial building (the main homestead) shortly after the turn of the century, which is furnished with the many antique pieces and artifacts from the family’s fascinating history. He mined tin on Mlilwane, was the largest employer of industrial labour in Swaziland for many years and brought electricity to Swaziland. He was known the locals as Machobane.

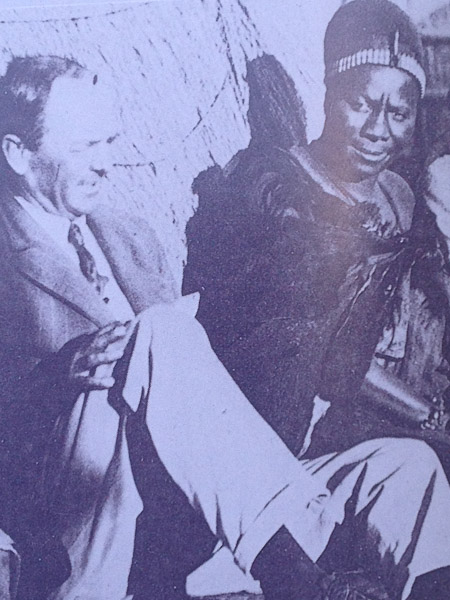

Ted Reilly – like his father Mickey, is also known as “Machobane”.

Billie Wallis, formerly Reilly, came to Swaziland in 1920 at the age of fifteen and married Mickey Reilly in 1925. She was, for many years, the only white woman between Mbabane and Manzini. Ted Reilly was born a native to Mlilwane in 1938 and became Swaziland’s pioneer conservationist.

The Reillys witnessed the disappearance of Swaziland’s game and this had a profound impact on young Ted Reilly. Between the rinderpest (or cattle plague) in 1896, excessive hunting, the ‘wildebeest plague’ in the 1930’s, poison traps, herbicides and insecticides, and unenforced game laws, the slaughter and depletion of Swaziland’s game and flora resulted to remnant populations in some areas and totally disappeared from others by the 1960’s. In less than a lifetime, from a wildlife paradise, Swaziland’s faunal wealth was reduced to the verge of extinction. The last wild animal was seen on Mlilwane in 1959 and something had to be done!

The only area available for a sanctuary was the Reilly’s own 460 ha farm which was then a highly productive mixed farming operation. Where the Rest Camp is now was a productive mealie land and tin mining added substantially to revenues. Having experiencing the spiritual values of wildlife, and seeing its escalating destruction country-wide, Ted Reilly decided to give up farming and turn over Mlilwane to provide a sanctuary for at least some of the Kingdom’s wild animals using limited personal resources and absolute dedication.

A huge tree planting operation commenced, a wetland system created (now known as the Hippo Pool), dams built, a furrow opened out and aquatic plants established, even dead tree stumps were planted for hole-nesting creatures. Then indigenous animals of all descriptions were ‘hunted’ for – from water scorpions, fishes, frogs and insects to whatever large animals remained to be caught and brought to the safety of Mlilwane. At this time, the Reilly’s approached His Majesty, King Sobhuza II for game from Hlane and that was the beginning of a long and very close personal association with the king who showed total support for Mlilwane and even donated animals from his own dwindling herds. The early days of catching game for Mlilwane are legendary and many tales, inevitably often exaggerated, are still told around the campfire. The rest camp was built on the 29th of November 1963 and opened to the public and 2 hard years later, on the 7th of January 1966, Mlilwane was gazetted as a game sanctuary under the agricultural act.

In 1969, Mlilwane was entrusted to a non-profit making trust, constituted for the benefit of the people and wildlife of Swaziland. On the 1st of April 1977, Mlilwane was proclaimed as a Nature Reserve under the newly created Swaziland National Trust Commission act of 1972, as amended. The commission also financed the ‘Hippo Haunt’ restaurant in the camp.

Mlilwane has grown to 10 times it original size through the support of the Monarchy, international support and true individual dedication and is a favourite destination for many people. Mlilwane has created entrenched conservation ethics for the Kingdom and the Swazi people are appreciative of all efforts at Nature conservation and have developed a pride in the natural heritage of their kingdom.

CELEBRATING 50 YEARS (www.kingdomofswaziland.com)

On the 12th July 1964, Mlilwane Wildlife Sanctuary opened to the public. This day marked the beginning of formal conservation in the Kingdom of Swaziland. At the time Swaziland was still a British Protectorate (Independence came in 1968). The country’s wildlife resource had been severely depleted and existed in remnant herds, largely on private farms. Wildlife was seen as vermin, a threat to the economic wealth of the country and thus there was no willingness to embrace the concept of conservation. One man, Ted Reilly, had watched the demise of Swaziland’s wildlife heritage. His experiences across the border in South Africa and further away in Zambia reminded him of how wild Africa could be. Reilly dreamed of a park system for Swaziland, safeguarding the rich diversity and beautiful landscapes.

With little support from the then British Government, it was down Ted to make it happen. With the support of Swaziland King behind him, a small force of rangers, and one, yes just one, land rover, Mlilwane was born. In no way was this an overnight operation though; conservation in Swaziland had a shaky and humble beginning.

When there was no game

Swaziland, with her rich habitat diversity, was once regarded as a hunter’s paradise, an un-tameable expanse with lion, elephant, buffalo and the likes roaming free. There are records of hunting licenses being sold for GBP 1 per season in 1906 and of a wildebeest “plague” in the 1930’s (more likely a natural migration) during which soldiers were deployed with machine guns to massacre the ‘vermin’ to safeguard cattle farms. Water troughs were often poisoned with the same aim, though killing much more than wildebeest and the 1940’s saw the Impala Express exporting 1000 impala carcasses per week! In a short two decades, by the 1950’s, the fruits of Swaziland’s land had depleted immeasurably to all but the odd scrub hare and duiker. Game had been plundered and removed for agriculture. Swaziland had all but lost her wildlife heritage. But, things were set to change. As a mere 20 year old Ted Reilly noticed an ever decreasing wildlife population each and every time he returned to his homeland. He had a dream to turn things around. Setting out almost entirely on his own, he followed his passion and five years later, aged 25, the now globally renowned conservationist opened Mlilwane.

50 Years of Conservation

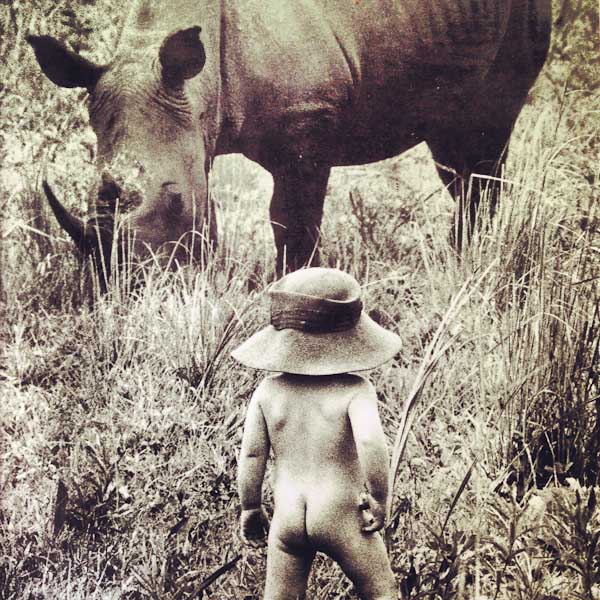

From 1960 Mlilwane started to grow, with habitat modification and the relocation of animals one-by-one. Work started at the beginning of the decade by putting up a large perimeter fence; keeping wildlife in and potentially harmful humans out. Once all the core elements of the reserve had been put in place, animal re-introduction began, the first phase of which include introduction of Impala, zebra, waterbuck, ostrich and kudu. After more animals were re-introduced including warthog and Nyala later in the decade, the reserve was officially opened by Hilda Stevenson-Hamilton. A year on, 1965, the first white rhinos were introduced.

Re-introduction and ongoing conservation work continued for the next 40 years, and is still an on-going project now. Swaziland’s reserves at present have all of the big five game animals; elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion, and hippos. The reserves are also home to some of Africa’s most iconic species. But, the work by Ted Reilly had a bigger impact than just a single park in what initially was a quite small back garden.

The concept of Swazi conservation and the dream Ted first had began in Mlilwane, but it was the success of this first project that lead on to the founding of Hlane Royal National Park, the establishment of the Swaziland National Trust Commission, and Mkhaya Game Reserve – now one of the worlds best Rhino success stories. With what had now become a flourishing country of wildlife and game parks, the organisation Big Game Parks was then established in the 1990’s as a private organisation, encouraging the establishment of further reserves such as Mbuluzi, Nisela, and Phophonyane. Today Big Game Parks is the delegated authority on the Game Act and CITES and operates a highly effective anti-poaching unit which is a key element to an on-going conservation success story.

Celebrating half a century

Ted Reilly’s initial ambition for Mlilwane was to create a reserve where families could enjoy the wonders of Swaziland’s animal heritage, and to provide an environment of learning and education. Over the next couple of months we’ll be revealing decade by decade the success of Mlilwane and the development of Swaziland’s Parks.

ARTICLES OF INTEREST

Ted Riley - an interview by Scott Ramsay 2014 in two parts (PDF)

Ted Reilly: A Living Legend, by Martin Dunn at The Conservation Imperative.

Go back to: Pioneers& Early conservationists