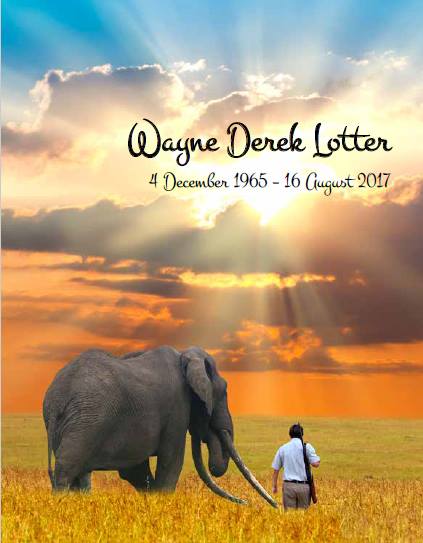

Wayne Derek Lotter

A dedicated protector of Africa's wildlife..

REMEMBERING A WILDLIFE HERO & FRIEND - Jane Goodall

I was profoundly shocked when I heard that Wayne Lotter, co-founder of PAMS Foundation, and known for his courageous fight against poaching of wildlife, had been shot and killed earlier this week in the Masaki district of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Wayne was a hero of mine, a hero to many, someone who devoted his life to protecting Africa’s wildlife. As a young man, he served as a ranger in his native South Africa before moving to East Africa to fight poaching, especially elephant poaching in Tanzania.

It was in 2009 that he teamed up with Krissie Clark and Ally Namangaya to form the PAMS Foundation and since then they have worked tirelessly to fight both poachers and corruption. I knew of their activities long before I first met them in 2014 when the elephant poaching crisis was at its worst in the Ruaha National Park. At that time powerful vested interests were desperately trying to blacken Wayne’s name and close down the PAMS Foundation. I was asked to bring the issue to the attention of people who could help him fight this, including the American Embassy. Fortunately, his good name and that of PAMS was salvaged.

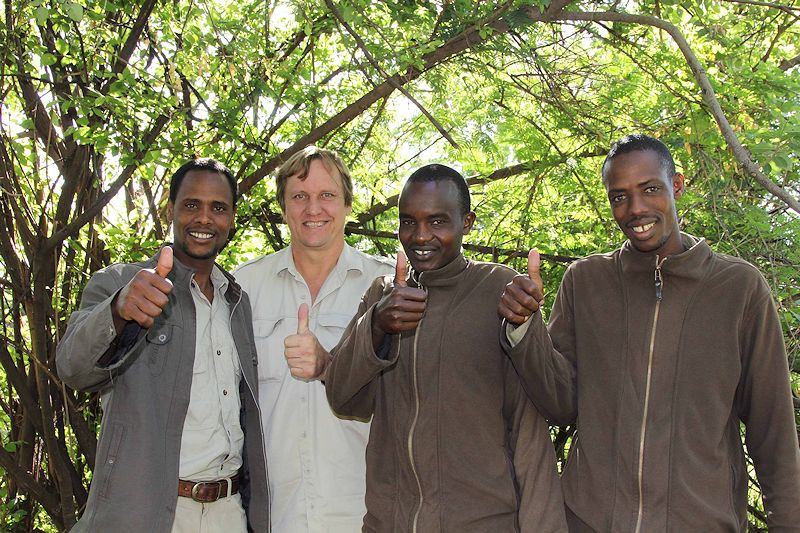

Wayne passionately believed in the importance of involving local communities in the protection of wildlife, and through his work with PAMS he helped train hundreds of village game scouts in many parts of the country. As a result, he gained the support of many of the local people, but inevitably faced strong opposition from dealers and many high-level government officials. He also worked to develop an intelligence-based approach to anti-poaching that undoubtedly helped to reduce the shocking level of elephant slaughter in Tanzania.

Wayne and his partner Krissie Clark have always been totally committed to their work, and have demonstrated, again and again, that they are prepared to carry on no matter what.

There is no doubt in my mind but that Wayne’s anti-poaching efforts made a big difference in the fight to save Tanzania’s elephants from the illegal ivory trade. Moreover, his courage in the face of stiff opposition and personal threats, and his determination to keep on fighting has inspired many and encouraged them also to keep fighting for wildlife.

If this cowardly shooting was an attempt to bring the work of the PAMS Foundation to an end it will fail. Those who have been inspired by Wayne will fight on. But he will be sadly missed by so many. My heart goes out to Krissie, his family and all who have been privileged to know and work with him.

Courtesey http://news.janegoodall.org/2017/08/18/wayne-lotter-remembrance/

Tribute paid to a brother in arms - Christiaan Bakkes

Wayne Lotter died bravely last week fighting for the cause he was most passionate about, the PAMS Foundation.

Lotter started his career in the late 80s as a trail guide in the Kruger National Park. One of his first colleagues, and later a South African wilderness writer, was Christiaan Bakkes. Bakkes, considered one of the best safari guides in Africa, was representing Wilderness Safaris as concession holders of the Palmwag Conservancy in Northern Namibia at the time. The men were in contact regulary. “Wayne Lotter was one of the rare breed of men,” he wrote. His iron resolve, principles and beliefs stood first and foremost above all else. He was never scared to challenge authority where he felt it was wrong. He was a free, unconventional thinker who had no regard for cheap popularity. He wanted to get the job done. I know of no other conservationist who got the job done more effectively than Lotter. “The high-profile arrests of top-level ivory traffickers in Tanzania were testimony to that. It made him feared and loathed by wildlife crime syndicates.“It cost him his life. Wayne and I were trail rangers on the Sweni wilderness trail in the Kruger Park for three years. Our shared passion for the wilderness and its wildlife bonded us together. Days spent tracking elephants and facing lions, and revelling in the wild nature around us made us friends. His eccentricities and unique wit would often crack me up in uncontrollable bouts of mirth.

“We parted ways and lost contact for years. The present continental poaching crisis brought us together again. I was proud of his success and wanted to be like him. We met and discussed this. I realised that the old carefree Wayne had crystallised into an unwavering, no-nonsense wildlife crime-fighter. There were no grey areas in his approach. It was either right or wrong.

“Wildlife crime cannot be fought without political will. Ambiguous conservation legislation leaves the door wide open for wildlife crime to flourish. The legal trade feeds the illegal trade. “Our last encounter was earlier this year on a wooden boat on Lake Malawi, sailing along the shore watching fish eagles swooping down. Our conversation varied from the present crisis to the memories of our youthful days in the veld. It was good. I am glad that I had the opportunity to tell him how proud I was of him. I am glad that our friendship was on a sound unbreakable foundation before he left. “We maintained weekly contact and he continued to inspire me not to give up. Our last correspondence was two days before he died. Wayne Lotter never deviated from himself. “Africa has lost one of its greatest and most dedicated conservationists. He was killed by cowards, the same cowards who are plundering our magnificent continent. Wayne Lotter went to another country to make a difference. He made great personal sacrifices. His colleagues and he faced incredible odds against a faceless enemy and succeeded. He disrupted their designs and filled their hearts with fear, so they sent an errand runner to collect the butcher bill. “Wayne Lotter’s death must not be in vain. He must never be forgotten. He must serve as the example that we must all live by. All of us who dedicated our lives to wildlife conservation. We must do his memory proud. We must not give up. “Waynie, you were a conservationist we all should aspire to be. If there were more of you, our troubles here would be over. I love you and I mourn with your family and friends. Rest well, my brother.””I salute you.”Conservation hero (from The Economist - August 2017)

Wayne Lotter, 51, was shot on Wednesday evening in the Masaki district of the city of Dar es Salaam. The wildlife conservationist was being driven from the airport to his hotel when his taxi was stopped by another vehicle. Two men, one armed with a gun opened his car door and shot him.

No landscape was dearer to Wayne Lotter than the savannah of southern Africa, and in particular one corner of it, the Selous-Niassa Wildlife Corridor round the Ruvuma river in Tanzania. He cherished it from the air, circling in a microlight over the dry rolling plains, the miombo woodlands, the white river bed and the bright-green hippo marshes; he surveyed it from lurching Land Rovers and on foot, brushing his way through the tall elephant grass. Sometimes he was the only human, and even he was in his khaki ranger’s camouflage. Almost invisible, he would listen to the voices of the elephants and lions that really ruled this place.

Too often on his sorties, though, his stomach would start to knot. An elephant would scream out, alerting the herd. Or, on a breeze, he would catch that smell. It was a stench that hit you from 100 metres away: rotting elephant. And there, soon enough, would be the carcass, swollen in the sun, too much meat even for the scavengers to keep up with. The face would be hacked off with an axe or machete and the tusks, of course, would be gone.

Over his time in Tanzania he found hundreds of such carcasses, sometimes 14 in a day. He never got used to it. But he had landed in the world’s hotspot for ivory poaching: between 2009 and 2014, Tanzania lost 60% of its elephants. Astounded by the slaughter, he and two colleagues, Krissie Clark and Ally Namangaya, founded the Protected Area Management Solutions (PAMS) Foundation in 2009 to do what they could to slow it down.

He had spent long enough in conservation—25 years, much of it in Kruger National Park, his first love from childhood, and in Kwa-Zulu Natal—to know that simply throwing money at policing was woefully ineffective. It was stupid to address just the symptom, the poaching, rather than the causes. He was fighting networks that stretched from poor villages in the wildlife areas to fancy shops in Beijing and ivory-carving factories in Vietnam, involving not only the poachers and the henchmen who controlled them but corrupt individuals in government, the judiciary, the police and, he insisted, even NGOs and conservation departments. His biggest problem was that almost no group or institution was clean. At the village end, poachers flashed their money and lured in other young men; at the Far Eastern end, demand was insatiable. As fast as the rangers armed themselves, the poachers went one better, toting Kalashnikovs against single-shot rifles. Penalties for their crimes were laughably light; ivory left the Selous in an unending stream. Even if he lopped a head off this octopus, he would find several legs still hard at work.

To fight this, he proposed an idea he had first heard from a detective in South Africa: when investigating a crime, create a network of informants. His were local people, incentivised with uniforms, cash and GPS devices to patrol in a buffer zone round their villages, recording the movements of elephants and also of their would-be killers, intercepting them and their rifles before they even reached the park. He wanted scouts to mingle, too, with the poachers living in their villages, finding out so much about them that, when arrested, they would instantly spill the beans on their paymasters. After all, the ivory they were paid five euros a kilo for was going for 2,000 euros in China.

He made little of his role, though. When Leonardo DiCaprio asked him to appear in his documentary “The Ivory Game” in 2016, he told him to film his village rangers instead. They did it all; he was just the one who went round, joking despite his anger, to ginger people up. He was fighting a war and, as in a war, he wanted his NGO to be nimble and unpredictable—no place for a collar and tie, which he barely knew the use of. The more ponderous and narrowly focused a conservation outfit was, the more easily poachers could corrupt it.

The gunman who forced his taxi door and shot him on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam probably killed him for his work. He knew it could happen; he had death threats all the time. With typical bravado he ignored them, and just went out again to watch with a cherubic smile a herd of elephant making their way across the Tanzanian savannah, safer than they were.

This article appeared in the Obituary section of the print edition of The Economist under the headline "The Ivory Game".

The work of the PAMS Foundation continues

The PAMS Foundation funds and supports Tanzania’s elite anti-poaching National and Transnational Serious Crimes Investigation Unit (NTSCIU) which has been responsible for arrests of major ivory traffickers including Yang Feng Glan, the so-called “Queen of Ivory” and several other notorious elephant poachers. Since 2012, the unit has arrested more than 2,000 poachers and ivory traffickers and has a conviction rate of 80%. The NTSCIU was featured in the Netflix documentary 'The Ivory Game', with Lotter believing that its work had helped to reduce poaching rates in Tanzania by at least 50%.

The latest elephant census data suggests that elephant populations fell by 30% in Africa between 2007 and 2014. Tanzania experienced one of the biggest declines in elephant numbers, where the census documented a 60% decrease in the population.

Lotter rarely took credit for PAMS’ success in helping reduce poaching rates in Tanzania, and was always quick to credit the work of the communities and agencies he worked with.

Lotter was a big figure in the international conservation community, having served on the boards of several conservation groups and was the Vice President of the International Ranger Federation. The news of his death has sent the community into mourning. “Wayne was one of Africa’s leading and most committed conservationists. He had over two decades worth of experience in wildlife management and conservation, and can be credited as the driving force behind ending the unscrupulous slaughter of Tanzania’s elephants,” said Azzedine Downes, CEO of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW).

“Wayne devoted his life to Africa’s wildlife. From working as a ranger in his native South Africa as a young man to leading the charge against poaching in Tanzania, Wayne cared deeply about the people and animals that populate this world,” a statement released by the PAMS Foundation team stated.

and PAMS co-founder Krissie Clark.jpg)